Mark Newport is based in Michigan, but he flew to Santa Fe for the opening of his form & concept solo exhibition, Mending. The show features torn muslin cloths that Newport patched back together using intricate embroidery techniques. The painstaking task was an opportunity to meditate on the vulnerabilities of the human body, and the miraculous process of scarring. While he was visiting Santa Fe, we sat down for a conversation about his career, the fiber art community, and how his bodies of work link together.

Could you tell us a little bit about your background in art-making?

I did my Bachelor of Fine Arts work at the Kansas City Art Institute, and took a few years off and then I went to the School of The Art Institute of Chicago for my graduate education. I graduated in 1991. Since then, I’ve lived in several different cities and made work in all of them.

What are you up to now?

Currently I live and work in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan where I am the head of the Fiber Department and Artist in Residence at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, which is a graduate program for people studying in my department. I maintain my studio practice there.

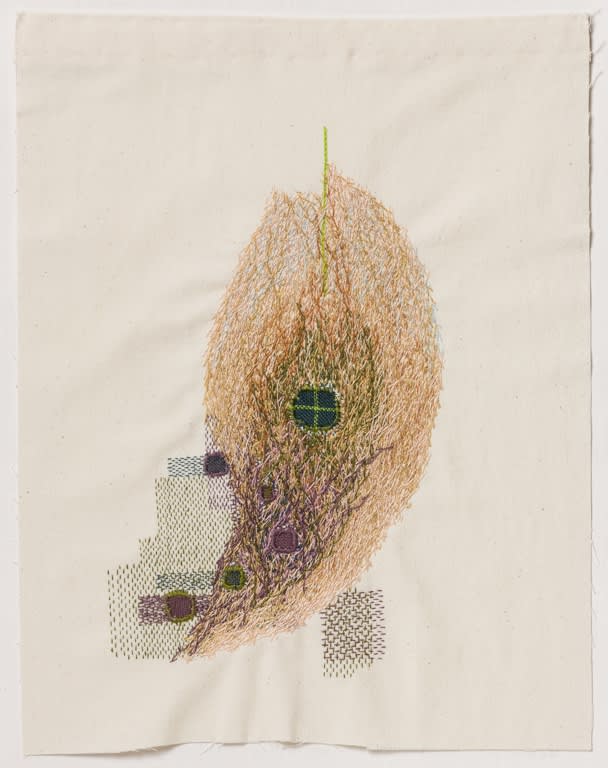

Mark Newport, Mend VII, embroidery on muslin

What do you mean by ‘Artist in Residence’?

The term Artist in Residence at Cranbrook is kind of equivalent to an assistant or associate professor at the university. It denotes that we’re teachers, but also that we’re mentors. So, Artists in Residence is meant to assert that I’m an artist, and I work there teaching. Cranbrook is kind of based on the old mentorship-guild way artists were trained in Europe in the pre-modern era.

What inspires you about the contemporary fiber art community right now?

I think what’s interesting about fiber right now is that it’s hard to identify what fiber is in some ways. If I take for example some of my students, there’s people doing video work that looks performative, there are people doing fashion work, there are people that are weaving and quilting. And, obviously, with the weaving and quilting you recognize that it’s coming from fiber and textiles. But, as has been the case for many years, there’s this sort of expanded idea of what that can be. And it becomes much more about the concepts and the ideas. And of course technology plays into that. You could be weaving with a Jacquard loom that is basically running from a computer program. Or doing digital work in video or doing something that’s completely digital and doesn’t have a physical presence but it relates to either the manufacture of or the history of textiles and what that means in the world right now.

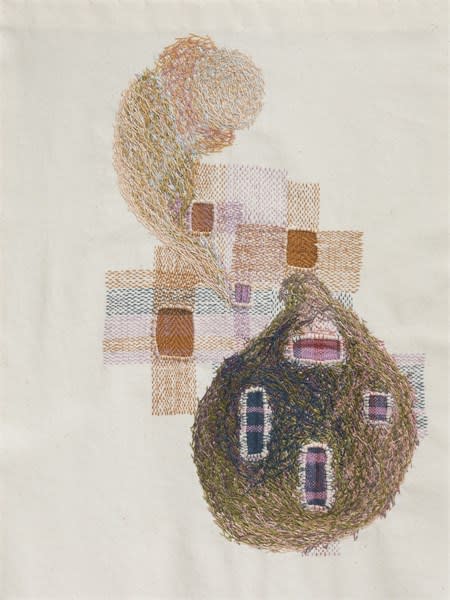

Mark Newport, Mend VIII, embroidery on muslin

In your work, you tend to chew on the same question or themes for years. Could you talk about your different bodies of work?

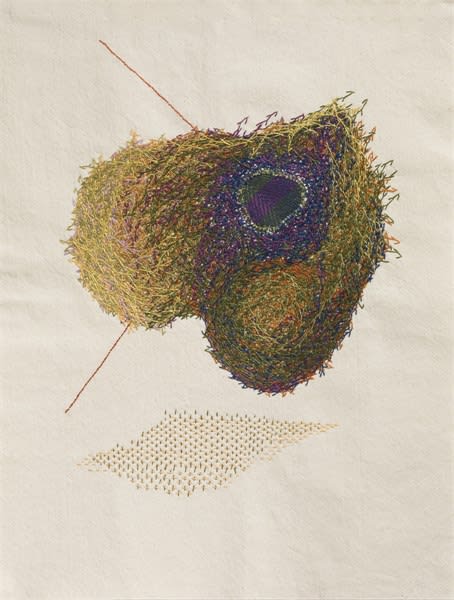

This year when I had to start school and give a lecture about my work, I jokingly said that I’ve worked on the same ideas for 25 years. That’s true in the sense that I’m interested in gender and how that relates to how we as individuals get to operate in the world or understand the world. I’m also interested in how the body relates to those ideas. The body can project a certain kind of idea about, say, masculinity or femininity or the continuum in between those two poles. The body is also not just a symbol but a kind of tool for recording experience. Our sense of touch and the way our skin works… records information through scars or wrinkles as we age. With the superhero costumes, I was using the idea of the pumped-up body deflated through the knitting, and relating it to an idea of gender in the body. With the new work, it’s this idea of scars.

Does your fascination with the body translate into scientific studies of the body? Are you on WebMD looking up skin conditions?

The fascination with the body means that I look at old anatomy texts. I love those old illustrations. I’ve done a lot of reading about how ideas of gender relate to how people depicted images of the body. At one point, scientists described the male and female genitals as the inverse of each other, even though they cut open bodies and saw that that was not the case at all. I love the idea that how we conceive of something isn’t always what we’re actually looking at, and how there’s slippage and contradictions there. I don’t go to WebMD, but I look at all sorts of videos about how surgeries happen and stuff like that, just to see what it is and figure out how things could be more informed in the work.

How do some of your more grotesque interests translate into this really subtle, gorgeous, detailed work?

The work’s not grotesque but the inspiration is, and I think that’s largely because I like to work with metaphor in this body of work. I like the idea that the muslin I start with is like my skin, but different. It holds things, it wrinkles, it gets torn, it needs to be fixed just like my body. And so, I’m using the tools that I’m trained to use to make something, and I don’t necessarily want it to be grotesque. I kind of like the idea that the reference to the wound on the body gets made kind of seductive and beautiful. People have the opportunity to process that idea in a different way.

Is there still a sense of wonder for you that wounds on the human body embroider themselves back together through scarring?

It’s absolutely fascinating. And to think about that in terms not so much of me, but my son who’s kind of accident prone, and watching that and how something heals. The body’s frustrating and amazing all at the same time.

You’ve been meditating on your own body and aging lately. Does that relate to your current body of work?

I don’t think that it’s an accident that this body of work is happening now. And after the costumes, I think I’m sensitive to the fact that being in my 50s makes me more aware of healing and of tending or taking care of myself and trying to last a little bit longer. I’m wondering how much can you tend, or fix, or repair, and how much you just have to accept and deal with. And I don’t think I would’ve thought that when I was making the other work, just because of how old I am now.