While some Americans have found themselves transitioning to remote work in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, many others struggled with unemployment. Another section of the population, however, found themselves on the front lines as Covid-19 continued to make headlines (and higher death statistics). In collaboration with CENTER, Santa Fe-based photographer and essential worker Eric Cousineau sought to document the people who continue to face the public, and the pandemic, day after day.

"In the beginning, it was just pure chaos," Cousineau says of his experience as an essential worker at Trader Joe's. "The store was wiped clean for the first two weeks. It was overly packed, just elbow-to-elbow. For the workers, it was exhausting." Read our interview below, and browse Cousineau's Essential Worker series and other recent works on his artist page. You can also watch a video of Cousineau discussing the series with CENTER Curator of Public Engagement Matthew Contos.

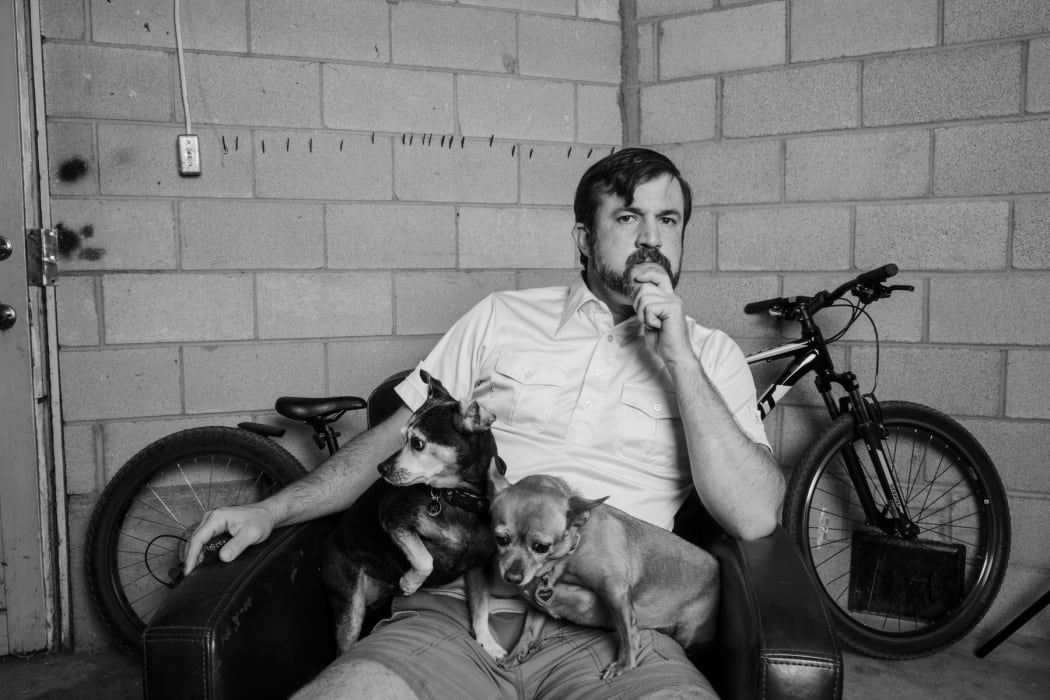

Eric Cousineau, Essential Worker Series: Colette Petit, archival pigment print.

How have you and your sons been faring in the pandemic era?

I’m either with my kids or at work. I haven’t even been downtown in months. I go to the store, I come home. I wasn’t very social to begin with. Being shut in, I’m doing what I normally do.

The kids know what’s going on. They’ve been busy with online learning, and for the most part they are okay with it. They’re like, “Okay, we’re home now.” I’m like, “Good talk.” They have their video games, their technology. I have two boys and they’re each other’s best friend. They keep each other entertained, it’s not like I have to worry about socializing them with many other kids. We have gone on a few bike rides with a kid who lives down the street, but that wasn’t until recently.

You’re a full-time employee of Trader Joe’s, which means you’re an essential worker. Could you describe that experience so far?

In the beginning, it was just pure chaos. The store was wiped clean for the first two weeks. It was overly packed, just elbow-to-elbow. For the workers, it was exhausting. Shipments weren’t coming in, our supply chain kind of dwindled because there was so much demand that the warehouses couldn’t keep up.

Then all the mandates started happening, and it became less stressful to come to work. Right now we only allow 50 people in the store at a time. That’s recent. For a while, we could only allow about 35 people at time. It made things less stressful, but it also made the day a little more boring, because the product wasn’t moving off the shelves as fast. A bunch of crew members are there expecting a busy day, and all of a sudden we have to slow down because stuff isn’t moving as fast as it once was.

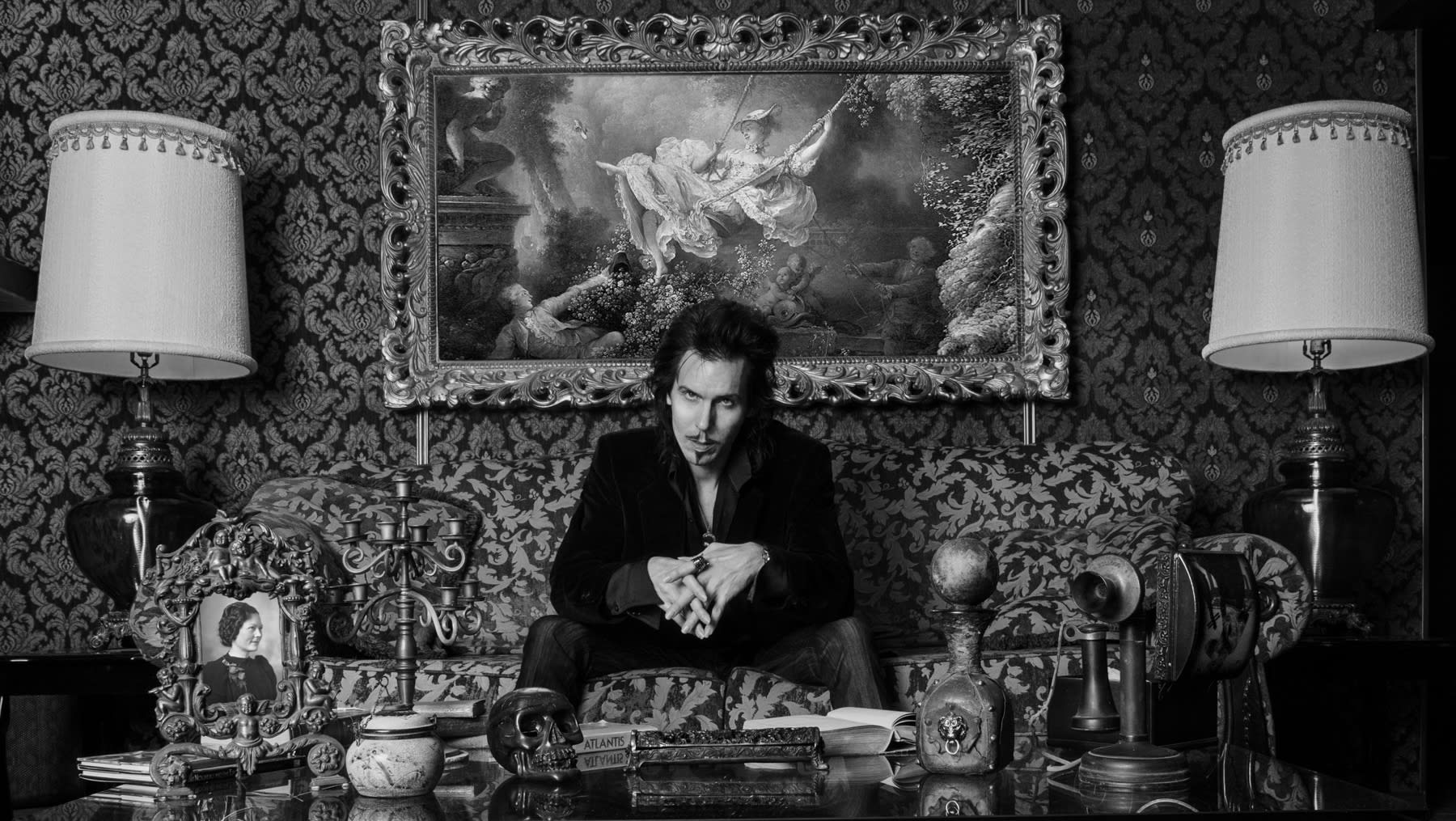

Eric Cousineau, Portraits: Gretchen Yatsevitch, archival pigment print.

Right before Covid-19 hit, you were deep into a portrait project that involved photographing friends, acquaintances and strangers in their domestic spaces around Santa Fe. Obviously that’s on hiatus now, but what inspired you to do it?

The reason that I did it is because I have social anxiety. I have a hard time interacting with people for the most part. If I go to a party, I can’t wait to get the hell out of there. I don’t really allow myself to be too close to people, because of events that have happened in my life. Doing the portrait project was forcing me to socialize, to talk to people and interact.

I chose the home setting because I liked the fact that I was photographing their personal space, what they thought looked good. I just kept asking and asking people. Sometimes I was doing six or eight portraits a day.

I used to photograph weddings and do portraits of couples. With the portrait project, I let the subjects direct themselves. They’re like, “What do I do?” And I’m like, “I don’t know, do what makes you feel comfortable. I’m not in control of your body.” They would just move around and I would photograph as they moved around. I would average around 75 frames. So I wouldn’t take a lot of time. Then I would edit down from there.

You definitely get a sense of that collaborative energy when you view that series.

I’m trying to get away from how a lot of people make portraits in the art world, where the subject is centered, full body or a tight-up bust. I’m trying to incorporate the environment of the person.

Eric Cousineau, Portraits: Jack Atlantis, archival pigment print.

Why did you set those constraints?

A lot of people were like, “Is this going to take long?” I just didn’t want to make them spend 2 or 3 hours posing for me. The longest shoot I did was for an hour, and it was for an eccentric friend who wanted to do wardrobe changes. That one took about an hour. The shortest one I ever did was about ten minutes.

And then the pandemic hit.

Yeah, I’m not going to ask anybody right now, “Can I come over and take your portrait?” Pretty much everybody knows that I work at a high-risk job, so nobody wants to be around me. I figured if I’m going to do any more portraits, they’re just going to be outdoors.

Eric Cousineau, Essential Worker Series: Thomas Luke Marcus, archival pigment print.

That brings us to Essential Worker, which is a very different kind of portrait project. How did that take shape?

Matthew Contos from CENTER emailed me sometime at the end of March asking if I wanted to do a collaborative project with CENTER honoring essential workers. I think my response without hesitation was, “I’m up for it.” The idea was I would photograph my coworkers at Trader Joe’s. Then Matthew would be in charge of putting up wheat paste photos on the windows and sidewalks outside Trader Joe’s so customers could view the photos as they waited in line to get in the store. The other idea was to project the images on a wall either inside or outside the store.

I told my boss a little bit about the project, and said Matthew would be contacting him to give him more details. My boss was all for it, but he emailed his boss to ask about it. He was like, “That has to be approved by the director of marketing.” He started emailing the director of marketing within the first couple weeks at quarantine. No response, no response.

As the project progresses I want to approach the director of marketing again about being able to photograph my coworkers in the store. I really would love to be able to include them in the project.

AS YOU RECENTLY TOLD THE ALIBI, THAT DELAY IS WHAT LED YOU TO REACH OUT TO OTHER TYPES OF ESSENTIAL WORKERS. IT STARTED WITH YOUR MAILMAN, AND THEN YOU EXPANDED TO TRUCK DRIVERS, NURSES, BUTCHERS ETC. WHAT ARE SOME SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS YOU HAD TO MAKE DURING THOSE SHOOTS?

It’s a little bit different, because you don’t get to see the person’s whole face. You just get to see their eyes. The portrait of the mail carrier I took, he doesn’t have a mask on. When I’m composing the photo and in the room with the person, I have to keep in mind that I have to be six feet away from the person. I couldn’t move in closer if I wanted to.

I have to factor all of those things in, and I don’t want to be there for long. I don’t sit down and talk to the people that much. I’m like, okay, “Let’s do this and I’m out of here.” I also have the fear in the back of my head that I could be infected, even though everyone’s taking a lot of precautions. Because of my job as an essential worker, I think I have a little less fear of the virus, but it’s still there.

Eric Cousineau, Essential Worker Series: Pierre Mahieu, archival pigment print.

What are some other series you’ve been working on lately?

When the initial chaos of the coronavirus set in, I was trying to think of things that I could still photograph. What if I just start photographing random objects in my house? Then it moved on to, should I photograph flowers or something? No, there’s way too many photographs of flowers. I’m like what about the roots of plants?

I just started with a few plants that I have in my house. Do I leave the ball of dirt on? I decided to completely clean it off the best I could, and photograph it against a white background and see what happens. I set up the white backdrop, a strobe, and I would hang the plants from the ceiling. I would have two buckets of water, and I would clean the dirt off the best I could, dry it, hang it up, photograph it. Then I would go back into the studio and repot the plant. So far, I’ve only killed one plant.

Is that how your artistic explorations typically begin—from a place of pure curiosity?

I’ve been thinking about it more about how I photograph and why I photograph that way. I haven’t quite figured it out. On my most recent walk, I was like, “Oh, mailboxes are cool. I’m going to start photographing mailboxes.” I’ll find something that interests me—roots, or trees, or dismantled electronics, or old motels—and just go for it. I’m obsessive compulsive sometimes. Once I hone in on something, I like the repetition of things.

A lot of photographers out there are trying to tell a story. They’ll have a landscape, a portrait, a closeup of an object that are a complete narrative when you view them together. Sometimes they’ll include text that explains their photographs. I’m not much of a storyteller in that sense.

Eric Cousineau, Dendrites 14, archival pigment print.

The way you arrive at a subject might be incidental, but your imagery possesses deep emotional undercurrents. For example, the Dendrites series seems to reflect our current chaotic moment so perfectly.

I started that series over the wintertime, when I just wanted to get outside and photograph. All the dendrite stuff is taken during the daytime, they’re not at night. I’ll use a high-powered flash and a really tight aperture to create that shadow and contrast. I started walking in the arroyo behind my house, photographing trees, and liking the composition of them. They almost feel like they’re underwater, which is what I like about them.

Someone pointed out they look like dendrites. I’m like, “What is a dendrite?” It has to do with branching neurons in the brain. I photographed that for a couple months in the wintertime, but I kind of want to do more in the summertime to compare and contrast when there’s leaves on the trees versus no leaves on the trees.

Could you talk a little bit about your American Motel series?

After I graduated from College of Santa Fe, I did a road trip with my friend and we went to a concert in Washington, D.C. We didn’t have much money, and we were staying in the cheapest hotels we can find. I’d be like, “Oh my god, this hasn’t been updated since 1972.” I became fascinated with how people decorated them and what people thought looked good. I was like, if I’m going to do this project, it needs to be in color.

A year later, I started the project with 4 x 5 color film. It was really sporadic, because I was starting a family, working. I’m not even technically done with the project, so someday when it’s possible to hit the road again I will.

I know the pandemic conditions really undercut your event photography business. How are you adapting as a professional photographer?

All I’ve ever wanted to do is be a photographer. I’ve never really, you know I have plan A and plan B. If plan A doesn’t work, I don’t have plan B. I shut down my wedding website and decided I’m going to focus on my artwork, and I got a lot happier.

I stopped worrying about how people expected me to photograph. Even recently, on Instagram, I unfollowed a bunch of photographers that are “making a living” at it. I’d obsess over it, how are they making a living, how are they photographing? I decided to stop looking at other photographers for a while and figure out my own style, and see if I can come up with something on my own. Maybe I will, maybe I won’t.