Julia Mazal, a Santa Fe, New Mexico native who recently enrolled at Bard College Berlin, is our new overseas correspondent. Read on for a dose of "art school confidential," and check back next month for another journal entry from Julia.

The Berlin Biennale was one of the things I was most looking forward to this semester. I had no expectations and had not done much research about it, but I was so excited to go to an art event after months of lockdown hibernation. They made it so that you had to buy your tickets online for each venue. You had to pick a specific time slot to keep track of the number of people going in and out, and obviously, masks were required.

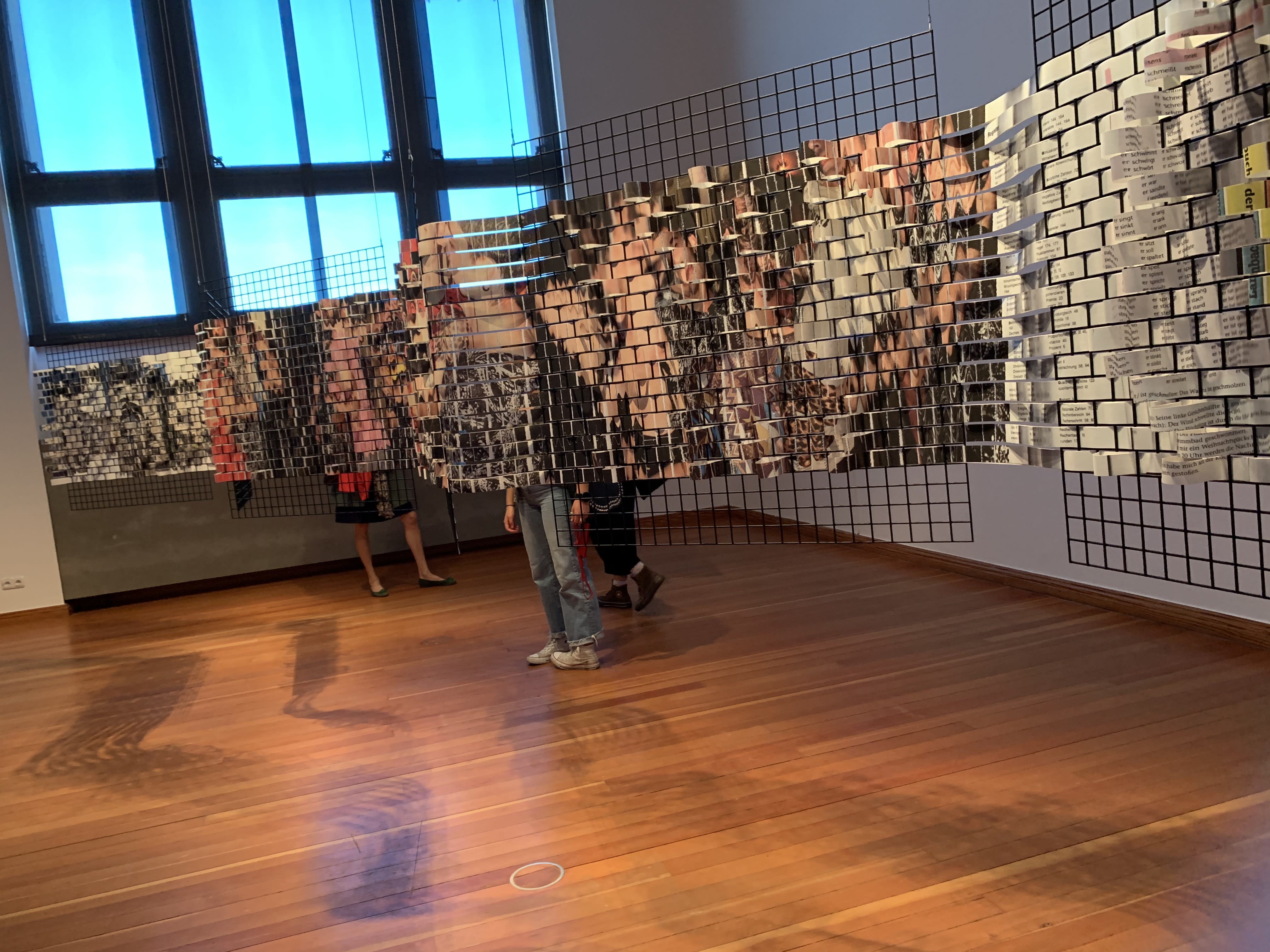

I bought tickets immediately, and the first venue I went to was at the famous museum in Potsdamer Platz, known as Gropius Bau, where they had the exhibition on the top floor.

The first two pieces we saw were by two Latin American artists, which both excited and surprised me given that they are not widely shown in Europe—especially emerging artists from the region. At first glance, the first room looked like one of those European anthropological museums that display non-Western objects that have clearly been stolen, but when we looked closer, we saw that they were made of paper, clearly meant to make a statement about such museums.

I thought it was incredibly clever to make this the first piece in the show because it reminded me of a discussion I had just had in one of my classes about an exhibition at the newly rebuilt Berlin City Palace featuring looted African art from Germany’s colonial era, which caused a lot of controversy. I don’t know if there was a correlation, but it was definitely a vital counter-narrative to shed some light on the issue!

As I walked through the show and read the descriptions of the art pieces, I began to see more and more Latin American artists, addressing issues like the post-colonial struggle, environmental injustice, and queer-phobia. I went to the exhibition with some friends, and two of them, like me, are Mexican. I remember we looked at each other surprised and proud of all of the representation. What can I say, I mostly expect to see the typical European modernist canon or young conceptual European artists when I go to museums here. Never had I seen so many artists from my region making such explicit, bold political statements.

One of my favorite pieces (shown above) by Bolivian artist Andres Pereira Paz, is an installation of what looked like bronze and mixed media sculptures accompanied by the sounds of the guajojo bird who had to escaped its native Amazonian habitat in Brazil due to the fires and found refuge in La Paz, Bolivia. That room was powerful, because the bird clearly was also a symbol for all of the environmental and colonial destruction in the region which has resulted in countless refugees who can never return home.

Although most of the exhibition was composed of South and Central American artists, there were also some artists from other parts of the world. For example, a Turkish artist named Aykan Safoğlu who went to a German school in Istanbul where Western ideals and notions of “freedom” were advocated for, but the origin of the school was actually based on strategic German/Turkish relations meant to “assert German cultural superiority” according to the description of the piece.

I found this piece to be extremely relevant as well because Turkish people are the largest minority ethnic group in Germany. In fact, the dӧner kebab is said to have been invented in Berlin by a Turkish immigrant. The gentrification of neighborhoods in Berlin inhabited by the Turkish population and the larger Arab community emphasizes this artwork's urgency, which addresses lasting tensions and discrimination against Aykan Safoğlu's community.

Then I realized that it is such a privilege to be seeing this exhibition because most of the artists themselves were not able to attend due to the pandemic. So, what does it mean for a prestigious institution like the Berlin Biennale to host mostly artists from the Global South, who won't even be able to attend their own exhibition?

It means the art world—as always—is reflecting the political atmosphere around us. It is time for better representation. It is time for non-Western art to be given a fair chance. My favorite room in Gropius Bau was the last one. When I walked in, I encountered many Chilean flags and pictures of Salvador Allende. Wow! I thought that this seemed bold for Berlin, which was “saved” by the United States in the late 1980s, but is now proudly exhibiting the art of Marxist resistance against the US-backed coup of 1973.

I know times have changed, and the Cold War has ended. Still, it's striking how visible this work was—I even glimpsed a passage of it through the museum's windows—considering Berlin's complex history.

The pieces in the Allende room (as I call it) are from the Museo de La Solidaridad Salvador Allende, a campaign designed to defend Allende from the CIA’s effort to discredit him. They asked artists from around the world to donate works to form an “anti-imperialist experimental art institution for the underprivileged of the third world," according to the description of the show. After the coup, the works were seized and the artists were exiled, and now the works are being shown in Berlin, it was quite fascinating to see.

The Allende museum's works fit wonderfully into the biennale's narrative because they were also exhibited in the other, smaller exhibition spaces I went to (C/O ExRotaprint and daadgalerie). This made me think that perhaps the curators unintentionally replicated the message of the experimental Chilean museum. There was a message of resistance and struggle, but instead of being in the context of an imperialist coup, it was in the context of a global pandemic.

Not surprisingly, the show was curated mostly by women, who are all based in South America and have focused on promoting women and queer artists from the region. So, in conclusion, I recommend attending the 11th annual Berlin Biennale, one of the only major art events that is able to be open in Europe at this time.

Curators:

Renata Cervetto, Agustín Pérez Rubio, María Berríos, Lisette Lagnado

My favorite artists:

Sandra gamarra Heshiki (Lima, Peru, Gropius Bau)

Andres Pereira Paz ( La Paz, Bolivia, Gropius Bau)

Aykan Safoglu (Istanbul, Turkey, Gropius Bau)

Flávio de Carvalho ( Barra Mansa, Brazil, Gropius Bau)

Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro (Vitoria, Brazil, Gropius Bau)

Cian Dayrit (Manila, Philippines, Gropius Bau)

Bartolina Xixa (Tilcara, Argentina, Gropius Bau)

Dorine Mokha ( Lubumbashi, Congo, C/O ExRotaprint)

Edgar Calel (Chi Xot, Guatemala, Daadgalerie)

Osais Yanov und and Sirenes Errantes ( Buenos Aires, Argentina and Berlin, Germany, Daadgalerie)

Naomi Rincon Gallardo (Mexico City, Mexico, Daadgalerie)

Julia Mazal is an 18-year-old student who just started her freshman year at Bard College Berlin to study art history. Julia was born in New York City to Mexican parents, and shortly after moved to Santa fe, New Mexico, where she grew up. Julia has always been fiercely independent and curious, so at 14 she decided to leave home and go to boarding school in the south of France, where she met people from all over the world and learned French. Upon returning home she applied to the United World College and ended up at the campus in Las Vegas, New Mexico. Now in Berlin, Julia is excited to discover the ins and outs of one of the most exciting art scenes in the world through her art blog for Zane Bennett Contemporary Art.