-

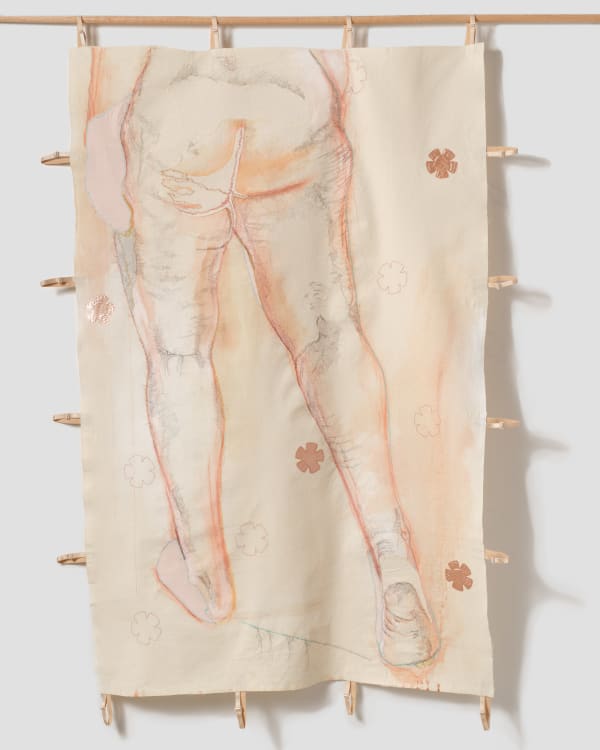

Cry, Die or Just Make Pies (Detail)

Cry, Die or Just Make Pies (Detail) -

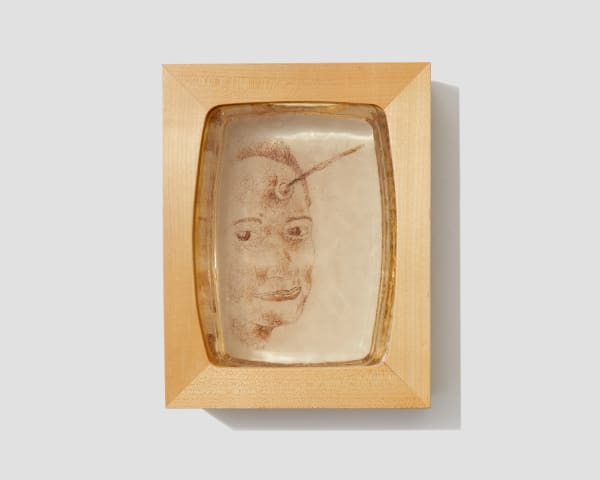

Phyllis & Aristotle (Detail)

Phyllis & Aristotle (Detail) -

Series Statements

-

Early Work

2001-2004"The depiction of women in art history informed these early hair artworks. In religious, mythological, and allegorical imagery, women manifest as dichotomous, & often sexualized, beings. They are both the virtuous virgin and the pernicious seductress: pure, moral, nurturing, erotic, sinful, and all-devouring.

As I worked, I began contemplating how the women of today reconcile historical representations of themselves to the contemporary, prescribed societal roles they occupy. In Phyllis & Aristotle, I depict the threatening power of women and recall the biblical stories of Adam & Eve and Samson & Delilah; stories that depict women as ill-intentioned saboteurs who wield unconscionable power over their male counterparts. In Swallow the Love, Spit Out The Seed, I allude to Roman Charity*, which renders women as the epitome of selfless devotion. Each work represents one side of the dichotomous female archetype found in Western literary and visual histories.

In Latinx culture, the often mythologized historical figure of La Malinche (Malintzin) personifies this dichotomy of feminine good and evil. Mother of all mestizos, the Indigenous woman Malintzin is often viewed as the Mexican Eve. Malcriada harnesses the symbolism of Eve in its depiction of the controversial Malinche."

–Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

*an ancient Roman moral exemplar in which a daughter provides her breast milk to save an aging parent from death. This dramatic action is used as a literary device to define virtuous charity.

-

Good Wife/Bad Wife

2004-2009"My studio practice explores the multidimensional female experience through the lens of varied sociocultural issues and experiences, such as divorce. In 2004, I navigated my own divorce. The legal and emotional process of divorce resulted in a sense of failure as a woman. My family reinforced this sense of failure by expressing their disappointment, which was deeply rooted in the cultural and religious idea that the roles of wife and mother are synonymous with womanhood. Unexpectedly, I found my long-held feminist beliefs & identity challenged by embedded cultural traditions. The dissolution of my marriage to another artist led to an examination of historical art partnerships such as O’Keeffe & Stieglitz, Kahlo & Rivera, and Mendieta & Andre.

This series, Good Wife/Bad Wife, contemplates the sociocultural role of the wife and its impact on women artists. While working on this series, I read numerous books on the intersection of marriage and art, including Art and the Crisis of Marriage: Edward Hopper & Georgia O’Keeffe by Vivien Green Fryd, A History of the Wife by Marilyn Yalom, and Naked by the Window: The Fatal Marriage of Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta. What I discovered during my research was that women artists suffered from the challenges of marriage that arose because of the evolution and transformation of the wife role.

In this series, I recontextualize some seminal works of iconic women artists or recognizable elements of their artworks. As this series took shape, a phrase from Marilyn Yalom’s book stayed with me: “To be a wife may no longer be a badge of honor, but it is far from a badge of woe.” Each piece in this series features a prominently displayed name patch to reinforce the identity of the artist alluded to. The patch is a symbolic merit badge honoring steadfast individualism within the confines of marriage."

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

-

Body Image

2010-2011"My referential sources for the human figure are multifarious: I have employed images from art history books, mass media, hired models, and even used my own body. This series, centered on body image, focuses on analyzing fetishized areas of the female figure in art history: breasts and buttocks.

An analysis of these body parts' symbolic meaning through history would raise questions about arbitrary notions of beauty and contradictory norms for the female figure. Alongside these considerations are symbolic cultural associations to breasts and buttocks. Historically, the breast has taken on different meanings and roles: sacred, domestic, political, and erotic. The breasts and buttocks in my artworks are embodiments of beauty that communicate ideas about ageism, eroticism, maternity, and sexism to the viewer. Shapes droop uncompromisingly, spread with the advancement of age, and twist into folds of melancholy skin."

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

-

Chicks with Guns

2012-2013"My series, Chicks with Guns, examines the relationship between femininity, sexuality, and violence in film and television. More often than not, mass media communicates female empowerment via seductive outfits and cold, hard steel. When working on this series, I began to question the nature of this empowerment: were these representations of women drawing on their femininity as a power source, or were they rearticulating gender stereotypes? Is there a discrepancy between the sexy, gun-toting babe and society's multifaceted reality?

Jiggle, Jiggle, Jiggle juxtaposes female silhouettes inspired by the 70s show Charlie's Angels and allusions to La ganchas. La gancha is a term used by the Mexican drug cartels and translates to the hook: la ganchas use their beauty to attract male kidnapping victims. Although la ganchas are often pawns in a violent and complex criminal underground, they are treated as ordinary criminals, being incarcerated for their involvement in kidnapping schemes. The lived experiences of la ganchas highlight the gap between the seductive myth of feminized crime and reality."

Cry, Die or Just Make Pies presents a nude woman brandishing a gun and knife with little context, creating a sense of suspense. Is she a predator or prey? Conventionally, nudity connotes vulnerability, yet in this artwork, the woman projects invincibility.

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

-

Intimacy Between Female Friends

2014-2015How does a platonic relationship between men differ from intimacy between female friends? In the modern age, intimacy is shaped by a diversification of visual images populating mass media: Images informed by prevailing stereotypes and the expectations of gender roles.

This body of work was created in response to those images, particularly those from "bromance" movies. As a genre, the archetypal bromance movie uses comedy to talk about emotional intimacy between men in a way that circumnavigates the suggestion of homosexuality. In her blog, Disrupting Dinner Parties, Feminism for Everyone, feminist writer Rosie Franklin says, “there are no neologisms for female platonic friendship the way there are for male friendship.” In these artworks, I am the main character rendered alongside women friends. We are engaged in the human activity of intimacy. The familiarity of intimacy is replicated in simple actions despite the complex nature of intimacy.

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

-

Gender-Based Burdens

2016-2018Historically, labor has been divided by gender. In pre-industrial societies, when transportation modes were limited, women frequently performed tasks such as collecting water and gathering fuel. Often, women carried these collected materials on their heads. They acted and were perceived as conveyors.

Illustrations of such labor can be seen in the recorded history of Western societies as far back as the illuminated manuscripts from the fourteenth century. Which made me think, what physical and abstract burdens do women carry in the 21st century? Weight hauled by women can take on a psychological shape of enormous proportions. In these artworks, abstract personifications of gender-based burdens weigh on women's heads.

Emma Sulkowicz #1 confronts the act of rape on a college campus and its aftermath in a digital age where anything can go viral. Circulated across the internet, the image of Emma Sulkowicz carrying her dorm mattress became a striking daily reminder of gender-based violence on college campuses. The image in Emma Sulkowicz #1 is of Sulkowicz carrying an oversized vagina. Ultimately, Sulkowicz’s act of resistance is one of survival and endurance.

In my family, gender-based burdens of violence and poverty have had a significant impact. In I’m the Wilderness, I’m the White Noise, a family member's face challenges the viewer's gaze. Gender-based burdens disproportionately affect women of color. The late Mexican poet Susana Chávez uttered these words to protest femicides in Juárez: “Ni una mujer menos, ni una muerta más.” Her words, “Not one woman less, not one more death”, became the rallying cry across Latin America.

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

-

Jane Anger*

2016-2018In her 2007 keynote speech at the National Women’s Studies Association Conference, Audre Lorde spoke about anger being “a powerful source of energy serving progress and change” and “Every woman has a well-stocked arsenal of anger potentially useful against those oppressions, personal and institutional, which brought that anger into being.” This series explores the idea that anger can be used as a tool for change.

I created Twelve Angry Women in response to the Brett Kavanaugh confirmation hearing; specifically, Christine Blasey Ford’s accusation of sexual assault. The work’s title recalls the 1957 film 12 Angry Men.

What You Whispered, Should Be Screamed centers on the #MeToo movement that spread on social media starting in October 2017. While #MeToo was amplified by Hollywood women, it began with Tarana Burke, a Black activist. Burke highlighted the fact that many women spend their entire lives in concealed and unconcealed sexualized environments. Fueled by the momentum of the #MeToo movement, thousands of women exercised their agency by sharing their stories of sexual abuse, and, most importantly, naming their abusers. The movement directly impacted women of color due to socio-economic limitations and cultural stigma.

Rage Becomes Her: The Power of Women’s Anger by Soraya Chemaly and Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women’s Anger by Rebecca Traister served as inspiration in my studio practice.

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

*Jane Anger, the title of this series, refers to a British writer who published the pamphlet Jane Anger, Her Protection for Women in the 16th century.

-

Agency

2019-2021Marching is the simplest use of the physical body as a political force. For this series, I re-examined the history of marches, particularly protest demonstrations led by women. Because individuals are subsumed by a larger group during a protest, you won't find identifiable faces in these works. There are, however, plenty of legs, which suggest the varying tempos, pauses, and motions of bodies during a marching demonstration.

The feminine figures in these works are nude to emphasize the vulnerability of physical bodies during a protest. Art-historically, partially nude women have served as political symbols. In Liberty Leading the People, Eugene Delacroix depicts Liberty as a robust figure with exposed breasts who holds the French flag high and strides over fallen soldiers in a dramatic appeal to French nationalism. Through visual proximity, Liberty's bosom becomes a discrete, corporeal representation of the heart of France. The physical comes to represent the abstract in much the same way that Liberty's flag represents the abstract body of the nation.

In my works, unlike in Delacroix’s infamous painting, the nude female body conveys not only defiance but vulnerability too. The bodies I show have blemishes on the flesh and evident signs of aging to illustrate the demographic diversity that makes up a protest march.

-

Miss Nalgas USA

2022-2023One aspect of my studio practice has been raising questions about stereotypical concepts of beauty. In Miss Nalgas USA I confront these stereotypes head on.

Miss Nalgas USA consists of a performance artwork, an art installation, and video artworks. As a performance, it featured contestants vying for the honor of Miss Nalgas USA 2022 (Miss Buttocks USA 2022). This invented beauty pageant focused on self-identifying women over 50. Graces, Nalgonas, Marías is the last artwork in this series. Graces refers to the three graces in art history, nalgonas is buttocks in Spanish, and Maria is a popular girl's name in Spanish-speaking countries. Three poses inspired by the Super Bowl performance of Jennifer Lopez and Shakira unfold across the black twill fabric. Figurative stances emphasize the desirable attribute of the Latina: a bodacious bootay.

The dual identity of Latina American, however, foists different, conflicting beauty standards onto the Latina body. These conflicting standards are best illustrated by American superstars J-Lo & Shakira, both of whom exist as singers and sexualized stereotypes of Latina bodies in the popular imagination. This concept of dual identity and related beauty standards is studied in From Bananas to Buttocks: The Latina Body in Popular Film and Culture, a 2007 non-fiction collection of essays edited by Myra Mendible.

The figurative forms of Miss Nalgas USA are hand-stitched and made with human gray hair to highlight socio-cultural notions that burden aging women, such as J-Lo & Shakira who were 50 and 43 respectively during their Super Bowl performance.

—Rosemary Meza-DesPlas

-

All Artworks

-

-

About the Artist

-

Headshot courtesy of Rosemary Meza-DesPlas.

Headshot courtesy of Rosemary Meza-DesPlas. -

Credits

Curatorial by Jordan Eddy & Rosemary Meza-DesPlas. Installation by Brad Hart and Christina Ziegler Campbell. Photography by Marylene Mey and Byron Flesher. Words by Rosemary Meza-DesPlas, with contributions from Spencer Linford.